Image 1 of 4

Image 1 of 4

Image 2 of 4

Image 2 of 4

Image 3 of 4

Image 3 of 4

Image 4 of 4

Image 4 of 4

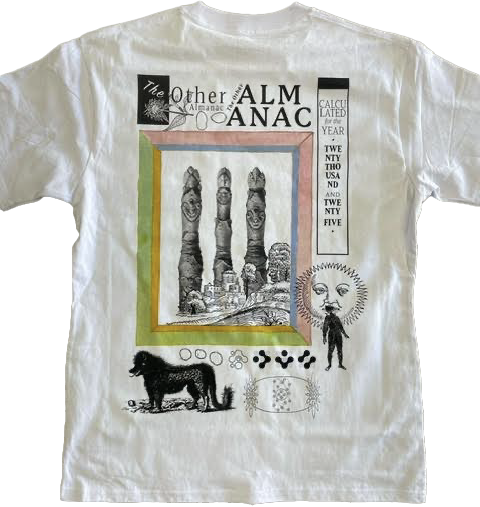

Kay Kasparhauser X The Other Almanac Tee

Shirt graphic is on the back of the shirt with a small logo on the front pocket.

Our first ever Other Almanac T-Shirt! A true future collectible. We couldn't be more excited to partner with three-time almanac contributor and one of our all around favorite artists, Kay Kasparhauser.

Kay pulled and designed images to create a mesmerizing collage of botanical, literary, and cultural sources from across time and space. Read more to learn about some of the images she used.

Available in black or white!

Karl Blossfeldt's Urformen der Kunst (1928)

At the grand old age of 63, just four years before his death, Karl Blossfeldt produced his first photography book, Art Forms in Plants. The book's 120 plates display Blossfeldt's remarkable photographs of plants – varieties from Equisetum hyemale (Winter Horsetail) to Tellima grandiflora (Fringe cups) — all captured in extraordinary detail, as if under the microscope, frozen into new forms almost beyond recognition.

Johannes Hartlieb’s Book of Herbs (1462)

Harlieb’s Book of Herbs contains geographic, botanical, and medicinal information accompanying 160 illustrations. It's thought to be the only fully illustrated herbal from the incunabula period of German history. The cost of producing such an ornate book in this period makes it unlikely that these images were actually employed in a pharmacological setting — and, though beautiful, the floral illustrations’ crude style would have made it difficult to correctly identify various species in nature based on their likeness. Instead, Library of Congress curators suggest, the book was created mainly as a feat of visual representation.

Signs and Wonders: Celestial Phenomena in 16th-Century Germany

A German broadsheet of Celestial Phenomena from the Holy Roman Empire conveying all kinds of wondrous phenomena through woodcuts: “anomalies in the sun, moon, stars . . . stones and fire falling from the sky, rainbows, miraculous births, rains of blood" Some speculate that the prophetic attention to celestial bodies was sometimes fueled by ergotism — the fungal infection that swept across cereal grains in much of northern Europe. Ingesting these crops produced delirium, hallucinations of fire and religious fervor.

The Beast of Gévaudan (1764–1767)

In the 1760s, nearly three hundred people were killed in a remote region of south-central France called the Gévaudan. The killer was thought to be a huge animal, which came to be known simply as “the Beast." Not only was the Beast said to prefer attacking women and children (and above all small girls), according to firsthand accounts published in the press it often “removed the victim’s head and drank all her blood”, leaving nothing behind but a pile of bones.

Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater’s Occult Chemistry (1908)

A book by prominent theosophists Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater on their occult beliefs and findings in chemistry.

Their chemical method was — conveniently perhaps — “unique and difficult to explain”. Its clairvoyant aspect was based on a Yoga principle that one can reduce one’s self-conception to minute proportions so that very small objects appear large. The observer then simply draws what he sees on paper and his commentary may be taken down by a stenographer. It is much like somebody using a microscope and, in the view of its adherents, no less objective.

Although Besant’s and Leadbeater’s science is clearly misguided, their interest was obviously sincere, and their labour fairly exhaustive. At a time when there was no other means of “seeing” atoms, what is truly remarkable is that their visualizations so closely resemble those developed later by chemists relying on Niels Bohr’s theory of atomic structure from 1913 and laws of quantum mechanics not worked out until the 1920s.

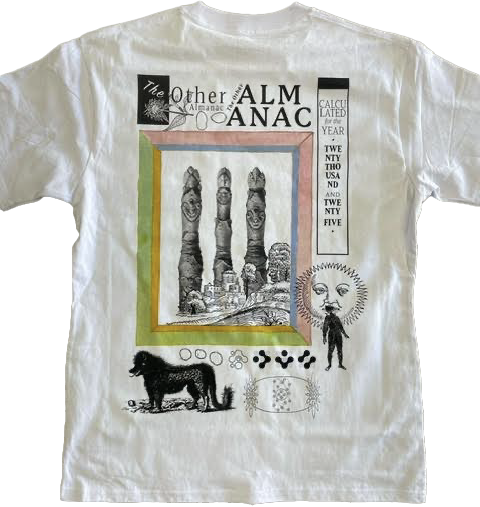

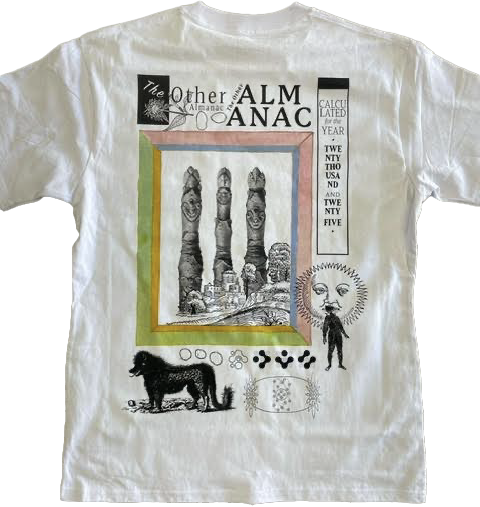

Shirt graphic is on the back of the shirt with a small logo on the front pocket.

Our first ever Other Almanac T-Shirt! A true future collectible. We couldn't be more excited to partner with three-time almanac contributor and one of our all around favorite artists, Kay Kasparhauser.

Kay pulled and designed images to create a mesmerizing collage of botanical, literary, and cultural sources from across time and space. Read more to learn about some of the images she used.

Available in black or white!

Karl Blossfeldt's Urformen der Kunst (1928)

At the grand old age of 63, just four years before his death, Karl Blossfeldt produced his first photography book, Art Forms in Plants. The book's 120 plates display Blossfeldt's remarkable photographs of plants – varieties from Equisetum hyemale (Winter Horsetail) to Tellima grandiflora (Fringe cups) — all captured in extraordinary detail, as if under the microscope, frozen into new forms almost beyond recognition.

Johannes Hartlieb’s Book of Herbs (1462)

Harlieb’s Book of Herbs contains geographic, botanical, and medicinal information accompanying 160 illustrations. It's thought to be the only fully illustrated herbal from the incunabula period of German history. The cost of producing such an ornate book in this period makes it unlikely that these images were actually employed in a pharmacological setting — and, though beautiful, the floral illustrations’ crude style would have made it difficult to correctly identify various species in nature based on their likeness. Instead, Library of Congress curators suggest, the book was created mainly as a feat of visual representation.

Signs and Wonders: Celestial Phenomena in 16th-Century Germany

A German broadsheet of Celestial Phenomena from the Holy Roman Empire conveying all kinds of wondrous phenomena through woodcuts: “anomalies in the sun, moon, stars . . . stones and fire falling from the sky, rainbows, miraculous births, rains of blood" Some speculate that the prophetic attention to celestial bodies was sometimes fueled by ergotism — the fungal infection that swept across cereal grains in much of northern Europe. Ingesting these crops produced delirium, hallucinations of fire and religious fervor.

The Beast of Gévaudan (1764–1767)

In the 1760s, nearly three hundred people were killed in a remote region of south-central France called the Gévaudan. The killer was thought to be a huge animal, which came to be known simply as “the Beast." Not only was the Beast said to prefer attacking women and children (and above all small girls), according to firsthand accounts published in the press it often “removed the victim’s head and drank all her blood”, leaving nothing behind but a pile of bones.

Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater’s Occult Chemistry (1908)

A book by prominent theosophists Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater on their occult beliefs and findings in chemistry.

Their chemical method was — conveniently perhaps — “unique and difficult to explain”. Its clairvoyant aspect was based on a Yoga principle that one can reduce one’s self-conception to minute proportions so that very small objects appear large. The observer then simply draws what he sees on paper and his commentary may be taken down by a stenographer. It is much like somebody using a microscope and, in the view of its adherents, no less objective.

Although Besant’s and Leadbeater’s science is clearly misguided, their interest was obviously sincere, and their labour fairly exhaustive. At a time when there was no other means of “seeing” atoms, what is truly remarkable is that their visualizations so closely resemble those developed later by chemists relying on Niels Bohr’s theory of atomic structure from 1913 and laws of quantum mechanics not worked out until the 1920s.